Está em inglês

Viviane Senna, a representante da família, tudo que envolve o nome de seu irmão tem que ter o aval dela.

Date: July 23 2011

Filme/Documentário Chapa Branca de Ayrton Senna

Asif Kapadia sips his latte and glances at the Tour de

France on the TV. We've been discussing Senna,

his biopic about the tragic Brazilian formula one motor racing star. After

winning the world cinema audience award for documentary at

the Sundance Film Festival, it has quietly become one of the most successful

documentaries released in Britain.

for documentary at

the Sundance Film Festival, it has quietly become one of the most successful

documentaries released in Britain.

It also played strongly at the Sydney Film Festival

and is poised for a US release that could put it in frame for an Oscar.''There's only one documentary we'll never overtake - Fahrenheit 9/11,'' says Kapadia, a Londoner, of the film's performance in his home country. Michael Moore's 2004 documentary has, like Ayrton Senna in the 1993 Brazilian grand prix, an unassailable lead in this race.

Kapadia's achievement is all the more remarkable in that his film is set in a sporting milieu often regarded as unremittingly snoozeworthy. ''The challenge was to make a film that appealed to people who think formula one is about men driving in circles in oversized cigarette packets,'' he says. ''I guess we must have done it.''

He's already thinking about the next project. ''I'd love to do a film about another sport. There's a story there,'' he says, nodding at the TV in a trendy London bar. ''The Tour de France would make a great movie

Getting permission to use old race footage was key to Kapadia's success with Senna. Improbably, the little-known filmmaker elbowed aside some of Hollywood's biggest names to make a movie

''Lots of filmmakers over the years approached the Senna family,'' Kapadia says. ''Oliver Stone, Michael Mann and I'm pretty sure Ridley Scott all approached and were told, 'No'. Antonio Banderas wanted to play Senna.''

Why were they rebuffed?

''The main thing was they all wanted to make a film about his final weekend at Imola in 1994. The family didn't want that. They preferred what we wanted to do, which was a three-act drama celebrating his life, from archive footage.''

The idea for the film came in 2004 when producer James Gay-Rees read an article about Senna on the 10th anniversary of his death. Gay-Rees and Kapadia pitched the idea for a documentary to the British production company

That husband was Manish Pandey, who became the writer on Senna. ''He's a surgeon but he's seen every race and knows every stat. So Manish and James worked out the story and pitched it to the family. Manish was such a fan that they trusted him like nobody else.''

Kapadia's CV didn't suggest he had what it took to direct a film about an adrenalin-charged sport, with a protagonist who lived fast and died young in a high-speed crash. He had made confident, quiet, leisurely paced art films - The Warrior, a 2001 Hindi-language feature set in the deserts of feudal-era Rajasthan, and 2007's Far North, a harrowing portrait of human loneliness in the Arctic wastes.

The little-seen Hollywood thriller The Return, starring Sarah Michelle Gellar, is the only blot on his re´sume´. ''I learnt a lot from that - this is show business, not show friendship,'' he says.

Kapadia knew a little about F1 before the film, he says. ''I remember when Senna died - I was watching it with my dad and sister at my parents' house … But you're right - I was an outsider to that world while Manish is like the guy in [a quiz show] when it comes to formula one, so there was a nice dynamic. And once we'd got the family's approval, that helped us get access to the archive of Bernie Ecclestone [the F1 tycoon].

''At one stage we had 15,000 hours of footage. We had to edit it down to 90 minutes - it took us four years.''

Kapadia's muted sensibility paid

''I wanted to make a film that wouldn't just appeal to formula one fans,'' Kapadia says. ''That's what the great sports documentaries do - Hoop Dreams, When We Were Kings - they're human dramas first, sport second, if at all.

''Lots of people who enjoyed it are not like [Top Gear presenter] Jeremy Clarkson. Often they're women who couldn't care less about motor racing.''

What captivates non-fans about Senna's character? ''That he wouldn't quit and he stood by what he believed in and yet had utter dignity. How many sports stars can you say that of? [Boxer Muhammad] Ali's the only other one. Ali was my hero - and my dad's - when I was a boy. And now I've made this film, Senna has become my hero too. There aren't many real heroes, you know?''

Senna, perhaps, is not so unlike Kapadia's earlier films. ''It's the story of an outsider - a Brazilian who came to Europe and took them on. A man who was slightly apart from the world he inhabited, a still centre around the noise.''

The film is not afraid of dealing with Senna's faith. ''My films often have a spiritual dimension, which comes from my Muslim background, and I'm happy to tackle that in cinema,'' Kapadia says.

He decided to have no talking heads, partly because he didn't want any retrospective rationalisation by his interview subjects. ''These guys [the racing drivers] hated each other, whatever they say now, and I wanted to show that.''

The film's central drama is the rivalry between Alain Prost and Senna - the former a Frenchman nicknamed the Professor for his coolly calculating approach to races, the latter determined to win at any cost. At the Japanese grand prix in 1990, Senna - angry and reckless - tried to overtake Prost on a chicane but the cars

''You can't excuse him,'' Kapadia says. ''He could have killed himself and Prost. I didn't want to judge him but to understand his motivation and to show the life-or-death nature of their rivalry.

''At some points when I was editing I was thinking of them as dramatic figures rather than people. Then I stopped.''

Kapadia says when he edited footage of Senna's mother at his funeral, his responsibility to the family became clear.

''I realised it's someone's life I'm dealing with and so, morally, I felt a responsibility for the images I've never felt before. If the family had objected to the film, it would have been very tough because I'd tried to make something honest and moving.''

The last act of the film deals with the cursed weekend at the San Marino grand prix at Imola in 1994. In footage from the starting grid, Senna looks haunted.

He was driving a Williams car

''Senna generally had his helmet on, looking straight ahead and focused at the start of a race. On that last day he chose not to wear the helmet and looked in such a state - he looks in the wrong place, he looks so lonely, so unhappy, so out of love with the sport.''

On that last day, Senna understeered at Tamburello corner, leaving the track at 305km/h then slowing down to 215km/h before hitting the wall. He died in hospital aged 34. Some think Senna had a death wish.

''I don't think he wanted to die,'' Kapadia says. ''There are people on my team who think God was saving him from himself because he's got to the position where he hates the sport so much and the only way out is to take him out.

''That's certainly one reading but I wish he'd walked away.''

The Guardian

Senna opens on August 11.

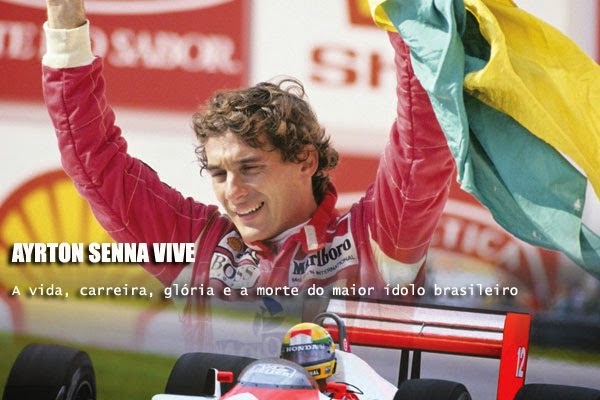

Ayrton Senna: charismatic champion

❏ Brazilian Ayrton Senna is considered one of the most

dazzling talents ever to take the wheel of a grand prix racing car❏ In 1991 he became the youngest driver to win three formula one world championships.

❏ When Senna - a 34-year-old known for his ferocious competitiveness and boyish smile - died while leading the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, the Brazilian president declared three days of public mourning. During the largest funeral in the country's history, traffic stopped on highways, trains halted on bridges and an estimated 3 million people lined the streets.

❏ Senna's millionaire lifestyle included luxury homes

❏ ''It's lonely driving a grand prix car but very absorbing,'' Senna once said. ''I have experienced new sensations and I want more. That is my excitement, my motivation.''

This material is subject to copyright and any unauthorised use, copying or mirroring is prohibited.

SOURCE

JEFFRIES, Stuart. Driven by hatred.

Disponível em: <http://www.theage.com.au/entertainment/movies/driven-by-hatred-20110721-1hpex.html?skin=text-only>.

Acesso em: 15 de novembro 2013.

Assista também o vídeo:

Senna

The Life of a Racing Legend

Asif Kapadia wasn’t even that big a racing fan when he began making Senna, one of the best sports documentaries of recent years, which rolls out this month to theaters around the country. But like many sports fans of a certain age, he knew the basic outline of the plot. Ayrton Senna was the Brazilian Formula One wunderkind who captivated the racing world in the late 1980s and early ’90s, fought a historic rivalry with French racing legend Alain Prost and died in a tragic crash in the prime of his youth.

It’s a story that seems tailor-made for a film. “The story just naturally had this three-act structure,” says Kapadia. “Most movies would end when he came out of nowhere to win the world championship, but that’s just the beginning of our film. That’s just the start. That’s easy. It’s what comes after, in the middle of the movie, the rivalry is really the heart of it. And then after that is the fateful weekend.” The characters are straight out of central casting as well: “Senna was a movie star. He had all of the looks, he had all of the talent… and we watched more and more of the footage, I was just amazed. First of all, I can’t believe a camera is there, and two, if we had written that, no one would have believed us. No one would believe Jean-Marie Balestre [the head of the racing governing body]. If you made him up, they’d say, brilliant character, but too over-the-top.”

Even so, the choice to make a documentary, rather than a narrative film, might seem surprising; Kapadia is a BAFTA-award winning narrative director (The Warrior, 2001), after all. And the word is that narrative directors from Ridley Scott to Michael Mann to Oliver Stone have pursued the project, and that Antonio Banderas has a long-standing desire to play the part. But, says Kapadia, that’s the rub: “You don’t get an actor to be Muhammad Ali. Muhammad Ali is the best Muhammad Ali. And you don’t get anyone to play Senna. It can be a feature film, but you have to make it a doc. So coming from a drama background, I felt very early on that we had an opportunity to make something that wasn’t a conventional, television-style talking heads documentary. We could make a movie. An epic movie.”

That desire to transcend conventional documentary conventions led Kapadia to possibly the most daring choice of all—Senna is told completely in the moment, with all period video from the late ’80s and early ’90s. The audio of recent interviews is mixed in seamlessly with audio of period interviews. I felt very strongly very early on,” he explains, “that I didn’t want to see any of these people and what they look like now, because it would pull you out of the feeling of being in a movie. When you go forwards and backwards and have people talking over stills, it becomes a bit like television to me. Because every frame of the footage was originally TV, I thought we had to do something, stylistically and aesthetically, to lift it into cinema. And my thought was, let’s never come out of that moment, and the tension and the drama will drive us through. And even if you know where it’s going, hopefully you forget along the way.”

It creates a magical effect, almost as if we’re watching reality as it unfolds, just in a compressed manner. By the time the film reaches Senna’s final race, the audience is sitting with Senna in that car, both emotionally and visually via his onboard camera. “He’s driving amazingly,” raves Kapadia. “It’s like he’s flying. There’s something transcendental and spiritual for me, in that last lap. It’s so moving. I’m not aware of any other cars, I’m not aware of any other people. The way he drives around that track is perfect. It’s the smoothest of the driving in the film. It’s like he’s just going to another place. I would show this film to editors, when we told them we wanted to do the film with all archival footage, and they’d say, ‘Yeah yeah yeah, that never works.’ And I’d show them some from the beginning, some from the middle, some from the ending. And quite few of them were Senna fans, and few of them had ever heard of him. And I’d get to that final lap, and all of them would be in tears. There’s just something inherently in that material that makes people cry.”

Words like transcendence and spiritual come up often in discussions about Senna, a deeply religious man who prayed constantly. “When you talk about religion,” Senna says in the film, “ it’s a touching point, very easy to be misunderstood … But I try hard—as hard as I can to understand life through God. And that means every day of my life—not only when I’m home but when I’m doing my work too.” He never failed to thank God for each victory, in a humble way rather than the current fashion for athletes. “It’s more than just putting it out there for the sake of it,” says Kapadia, “because if you look at the film, he really only speaks about God in Portguese. He stopped talking about God in English, because the English and the rest of the Europeans really jumped on him for it. Because when you’re doing 200 mph in a car, it’s so easy for someone else to say ‘Well, if you think God’s on your side, that’s dangerous for the rest of us.’ And Prost did say that. So Senna would do these press conferences in English after he won a race and say, ‘Yeah, everything went really well with the gears, and the brakes were going, and all this.’ And then in Portugese, he’d open up and be much more honest and personal, because he was speaking to people in Brazil. And it was a big part of him. It’s just another thing that if you had made it up, no one would believe you. He was a genius in the rain, and there were so many key races when he was losing and it would rain and give him time to catch up, and then he would win and it would stop raining.”

It’s that sense of Senna’s devout faith that makes his final accident seem both all the more heartbreaking, and simultaneously makes it bearable. He’s going to meet his maker, literally. The morning of that race, his sister recounts, he actually reads a Scripture that promises “That he would receive the greatest gift of all, which was God himself.” Kapadia muses: “The tragedy is, at the ending, it’s an act of God, the way he dies. It’s a series of incidences and freaks that had to happen in an exact way. Technically, something had to happen to the car, but then he had to hit the wall at a particular angle for the wheel to come off, and to come off at the exact angle to hit him in the head. No other injuries, nothing. If the wheel had missed him he’d be fine. That, for me, is an act of God. I don’t know what else to call it. For me, the spiritual element is a major thread all the way through, from the first time he gets in a car and thanks God for giving him the talent to drive the car. And throughout his career, he’s saying I thank God for doing this. And the very last time he’s in a car it’s God that takes him out of the car.”

“I knew the driver,” remembers Kapadia, of the days before he began work on this documentary, “but I didn’t know the man.” Thanks to this film, the world now knows the man, and is richer for it.

SOURCE

DUNAWAY, Michael. Senna The Life of a

Racing Legend. Disponível em: <http://www.paste.com/issues/week-8/articles/senna-the-life-of-a-racing-legend>.

Acesso em: 15 de novembro 2013.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário